“Hey James–I like your hat,” declared Henry Clifford as he sauntered up to the smaller boy on the playground.

James’ heart began to pound.

“I need a hat,” Henry continued, and the bully reached for it.

James dodged and began to run. Unfortunately, the direction away from Henry took him toward the street. James didn’t see the bread truck coming; parked cars blocked his vision. Neither did the driver see the boy.

James crashed into the vehicle with his head, denting his forehead like an eggshell hit with a spoon.

The surgeon warned James’ parents before attempting to remove bone fragments. “Prepare yourselves; there’s a strong possibility of brain damage.”

But the boy surprised everyone, sustaining no loss of function.

James endured three weeks in the hospital, followed by six months of recuperation at home.

He was fitted with an aluminum plate to wear over the wound, held in place with an elastic band. The doctor told him his head would remain dented, and he’d need to wear the protective head-gear for the rest of his life.

Of course, sports were out of the question, and as James grew up in the village of Twyning, England, he became increasingly withdrawn. He spent his leisure hours reading and writing stories.

James had always loved books; his mother taught him how to read before he started school. He especially enjoyed Agatha Christie. The year of the accident, 1933, James read all nine mysteries she’d written thus far. He was seven years old.

At age eleven, James balked at his parents’ continued protectiveness. Granted, he couldn’t play sports, but couldn’t he at least ride a bicycle? All the other boys his age had them. And why wear the protective plate (which generated plenty of teasing) if he couldn’t do anything anyway?

James was sure his arguments would win his parents over. The morning of his birthday he expected to come downstairs to shiny chrome spokes and gleaming Whizzer Maroon fenders.

Instead, sitting atop the dining room table was a second-hand typewriter. James’ mother stood in the kitchen doorway, a pained expression on her face.

“Please understand, son. If you injured yourself again, it could be even more serious. We just can’t take that chance.”

James’ father helped him heft the machine to his room where curiosity soon got the better of him. He began to type one of his stories[1]. And . . .

“It proved to be his best present and the most treasured possession of his boyhood”[2].

At age fifteen James refused to wear the protective head-gear any longer. If he was injured again, so be it.

James excelled in school and won a scholarship to Oxford University.

One evening he attended a church service nearby. Though James had read C. S. Lewis’ Mere Christianity and The Screwtape Letters, James realized he didn’t know Jesus. At the speaker’s invitation, he went forward to ask Christ into his life.

After graduation James taught at a college in London, but after two years, felt the need of further education and returned to Oxford.

James earned his master’s degree and was ordained deacon in the Church of England. He also wrote his first published article for the Evangelical Quarterly.

In 1954 James earned his doctorate from Oxford and married Kit Mullett, a nurse he’d met two years before. They would subsequently adopt three children.

Over the next twenty-five years James served in academic positions at three colleges, including Oxford, and as superintendent of an evangelical research center.

Always he was writing–publishing essays, articles, pamphlets, and dozens of books.

In the 1960s an editor asked James to write articles for Evangelical Magazine. He wrote 720 of them over the next five years. Some of those articles became his most popular book, published in 1973, with more than a million and half copies sold.

James and Kit relocated to Vancouver, Canada in 1979, for James to teach at Regent College. The next year James became senior editor of the magazine, Christianity Today while still maintaining his position at Regent.

Regent College today. Photo by Ken McAllister.

In 1997, Crossway Books invited James to serve as general editor of The English Standard Bible, published in 2001. He felt this was the most important work of his life.

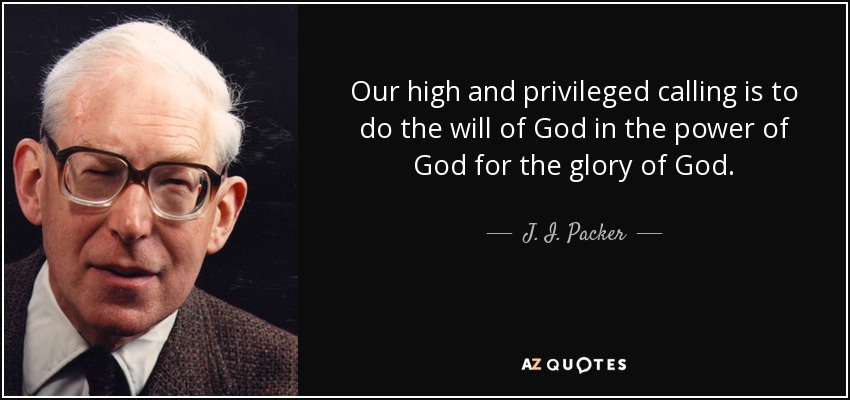

Upon James’ death in 2020, “readers of Christianity Today identified him as second only to C. S. Lewis among the most influential theological writers of the twentieth century”[3]. No doubt many of them had read that best seller, Knowing God.

And the influence they spoke of surely began to take root with that typewriter James hadn’t wanted.

But look what God did for J. I. (James Innell) Packer. Look what God did through him.

https://www.azquotes.com/author/17128-J_I_Packer

(Keep scrolling, please–important news below!)

[1] This story based on fact. Our pastor shared a brief version last Sunday; curiosity led me to learn more. See https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/blogs/justin-taylor/j-i-packers-11th-birthday-the-tale-of-the-bicycle-and-the-typewriter/

[2] Alister McGrath, J. I. Packer: A Biography, 6.

[3] https://www.samstorms.org/enjoying-god-blog/post/the-life-of-j-i-packer–1926-2020-

Additional source: https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/blogs/justin-taylor/j-i-packer-1926-2020/

Image credits: http://www.wallpaperflare.com; http://www.flickr.com (3); http://www.wallpaper.com; http://www.commons.wikimedia.org; http://www.azquotes.com.

Don’t forget the GIFT FOR YOU in the monthly newsletter–a “thank you” to faithful readers and newly-subscribed friends: Thirty encouraging quotes to inspire your own spirit and to share with others.

Scroll to the end of the newsletter to find this resource!