As Mr. Banerjee[1] sat talking with her father, Hannah bent over her needlework, taking pleasure in creating embroidery for a pair of slippers.

The visitor glanced Hannah’s way and couldn’t help but notice her handiwork—the stunning colors, beautiful pattern, and exceptional workmanship.

“Forgive me, Mohashoya” (respected lady), he said. “I must say your needlework is of superb quality. Might you be able to teach my wife how it is done? You could come to my home, perhaps once a week?”

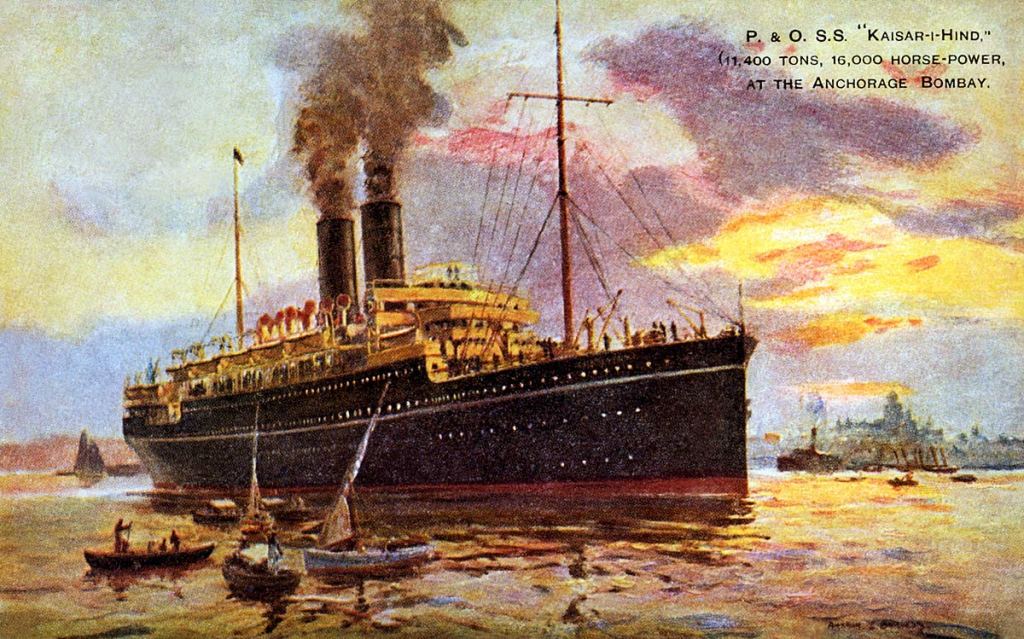

Hannah caught her breath. In that instant, God answered a two-decade prayer of her missionary family, serving in India in the 1800s.

Calcutta, near the northeastern border

Hannah had been born in Calcutta in 1826, and learned to speak the Bengali language fluently. By age twelve she was assisting her mother with the school they operated in their garden, taking responsibility for the younger students.

A deep passion began to grow within her for those who did not know Jesus, who lived without hope, peace, and joy.

In 1845, Hannah married Rev. Dr. Mullens, another missionary. Together they ministered to the citizens of Calcutta. She founded a boarding school for girls where they learned how to read and write, sew and embroider. They also studied the Bible.

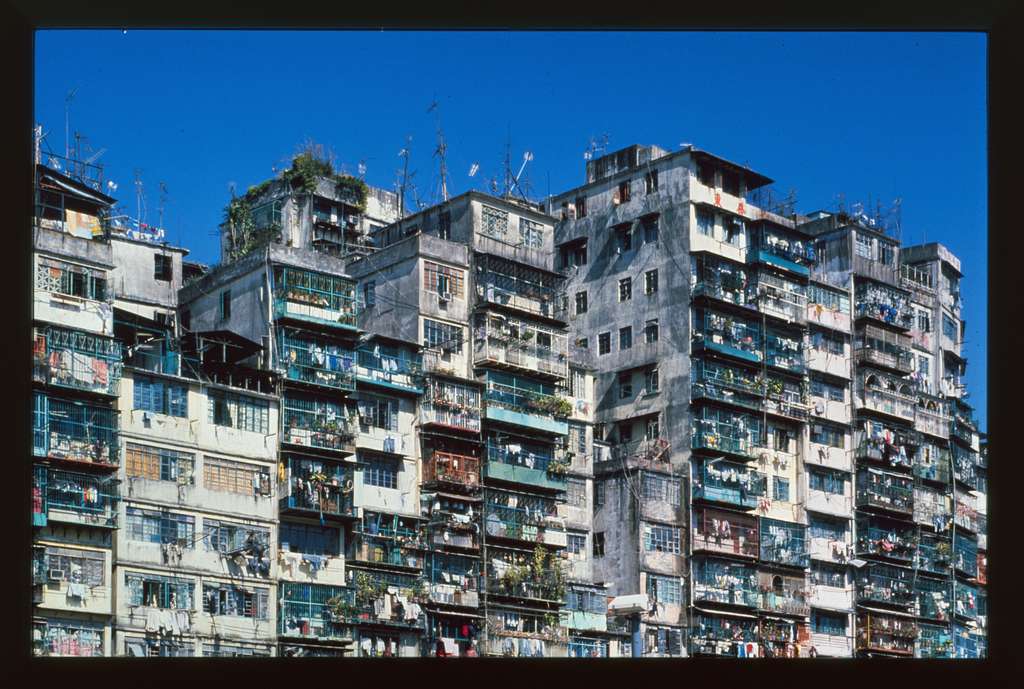

But their ministry to many of the women was hampered by the Hindu custom of confining them to the inner rooms of their homes, the zenana. Outer rooms were reserved for men and guests.

Women were considered helpless and beneath men, so they weren’t sent to school. Fathers arranged the marriages, often to a husband unknown by the bride. Many men practiced polygamy.

Within the zenanas, ill-treatment and neglect were prevalent. If on rare occasion these women went out in public, they had to be completely covered from head to toe.

Few opportunities presented themselves to tell them about Jesus.

But that afternoon, as Mr. Banerjee asked Hannah to teach his wife embroidery, she saw the grand opportunity God was providing. Before long, the sewing lessons with Mrs. Banerjee were accompanied by dialogue about Christ and what he offers.

Soon another opportunity presented itself. An acquaintance of the family, an Indian doctor, passed away, and Hannah went to visit his daughter.

To her delight, Hannah discovered the young woman to be highly intelligent. Her father hadn’t followed the zenana customs and had provided a tutor.

“Might you be willing to start a school for other young women?” Hannah asked. Before long, twenty young women were gathering to learn how to read and write, and to hear about Jesus. Hannah presided over the school.

Through gracious diplomacy, she gained access to other zenanas. Hannah’s mother assisted with the work.

Another woman became director of the boarding school, so Hannah could expand her ministry in the zenanas. At one time, she provided spiritual care for eighty women and seventy girls [2].

Nine years previously, Hannah had written a book for Bengali Christian women. In 1861 she began another book–this time for the women of the zenanas. But Hannah became ill and did not recover. She was thirty-five years old.

Some would question God’s decision. “Her ministry had just begun!” they’d say. But scripture explains God’s view. All the days ordained for Hannah, set before even one of them came to be, had undoubtedly been fulfilled (Psalm 139:16).

Many mourned the death of Hannah LaCroix Mullens, including 150 Christian converts from Hinduism who attended her funeral with their families.

Thirty-three years later, Rev. E. M. Wherry listed the following statistics for the Zenana, Bible and Medical Mission (established in 1880):

The mission “has 73 European missionaries and assistants, 54 Bible-women, and 149 native Christian teachers and nurses. It sustains 67 schools, with 2,554 pupils and three normal schools with 115 students training for mission work” [3].

Imagine Hannah’s joy to see these women (and perhaps thousands more) enter heaven, the ripple effect from that first visit with Mrs. Banerjee.

[1] Actual name unknown.

[2] Diane Lynn Severance, Her-Story, 247.

[3] From Women in Missions, American Tract Society, 1894, p. 117 (available online).

Sources:

Diana Lynn Severance, Her-Story, 247.

Image credits: http://www.needpix.com; http://www.ndla.no; http://www.canva.com (2).

Do sign up below for the monthly newsletter that includes a THANK YOU GIFT: Thirty encouraging quotes to inspire your own spirit and share with others.

Scroll to the end of the newsletter to find this resource!