Currently my prayers for others include healing from illness, avoidance of surgery, a smooth path ahead into a new life-phase, and guidance for an important decision.

Good things for good people.

But not long ago I had occasion to peruse Paul’s second letter to the Thessalonian church. Four times in three short chapters, Paul expressed his prayers for these Christians facing persecution and trials (2 Thessalonians 1:4).

His prayers surprised me.

Did he include protection from their enemies? No. Rescue from persecution? No. Lives of peace so they could share about Christ without threat? No.

Instead, Paul asked for God’s empowerment, encouragement, strength, understanding of God’s love, endurance, and inner peace.

Why were these qualities uppermost in his mind?

First, GOD’S EMPOWERMENT would help them live true to their faith (1:11 CEV), so they might honor God and God might honor them (v. 12).

And what might that honor look like? Shalom—which includes inner tranquility, divine wholeness, prosperity of soul, and more (1)—even during trials.

We too can ask God to empower those we pray for, that they might honor him, experience his shalom, and anticipate the supreme honor of hearing him declare, “Well done, good and faithful servant” (2).

We’d do well to pray the same for ourselves.

Second, GOD’S ENCOURAGEMENT AND STRENGTH would lead the Thessalonians to always do and say what is good (2 Thessalonians 2:17 GNT).

In the previous verse, Paul reminded these readers of God’s love and grace to them.

Perhaps he wanted to stir up memories of God’s goodness on display in the past, and once inspired, they’d be fueled to show goodness to one another within their church—to keep one another lifted up.

And that integrity would draw those outside the church to Jesus (3).

Third, GREATER UNDERSTANDING OF GOD’S LOVE AND ENDURANCE, provided through Christ (2 Thessalonians 3:5 GNT), would cause their confidence in him to grow.

Then, when challenges arose, the Thessalonian church would remain steadfast and unflinching in the face of persecution.

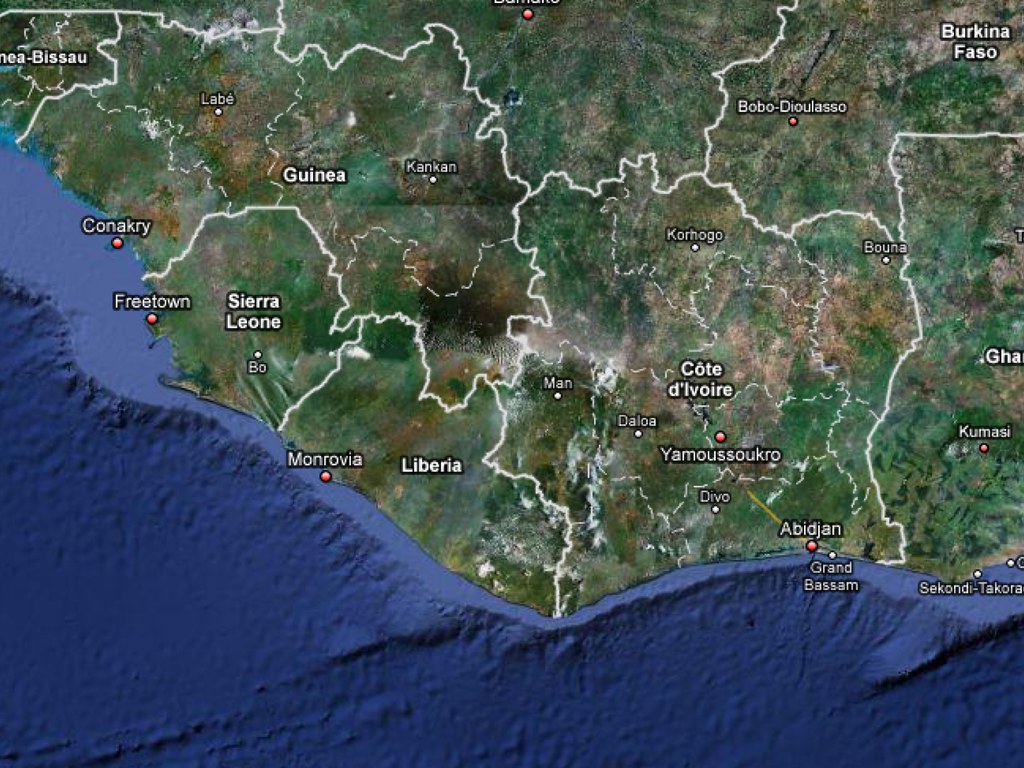

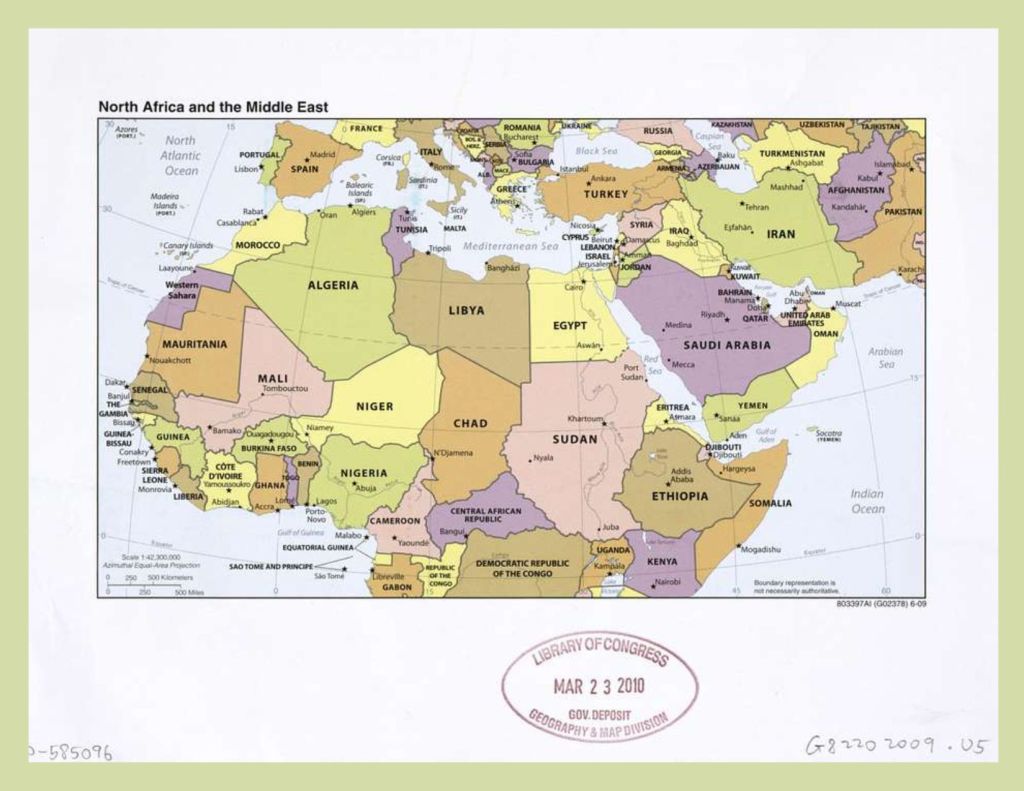

Down through the centuries Christians have suffered for their faith. Even now in Asia and Africa, Christ-followers bear up under imprisonment and torture.

Meriam Ibrahim was just such a prisoner, sentenced to death for refusing to become a Muslim. Her second child was born while Meriam was behind bars.

Finally her captors threatened to torture her with one hundred lashes followed by hanging, but Meriam later stated she never even considered acquiescing to her captors.

An international campaign for her release saved Meriam’s life. She now lives in the U.S (4).

Though we and our loved ones may never face such circumstances, we’re wise to prepare ourselves, and pray for endurance to stay the course—for all of us.

And last, PEACE—Shalom—from the Lord of Peace himself (3:16 HCSB).

Here shalom is not just alluded to; Paul prays for it specifically, that the Thessalonians might enjoy “at all times and in every way” this most sublime blessing.

No doubt, Meriam experienced such inner tranquility and deep, settled confidence. It can be ours also, as we stand on the strong foundation of:

- God’s promises. He is a refuge, a stronghold, who never forsakes those who seek him (5).

- God’s sovereignty and perfections. With flawless wisdom he always acts rightly (6).

- God’s power. Sometimes he rescues, as he did in Meriam’s case. Other times, in his wisdom of all things, he deems it best not to. It’s then we see his miraculous power to carry his followers through, as he has thousands of martyrs who’ve gone to their deaths praying and singing.

So what about our prayers for good outcomes and guidance? Are they improper somehow? Not at all. In another letter, Paul told us to pray about everything.

So I’ll continue to pray for D. to be healed, for N. not to require surgery, for C.’s path ahead to be made clear, and A., as she and her family look to God for guidance.

But I’ll also add God’s empowerment to persevere, his encouragement and strength to live with integrity in spite of challenges, to experience God’s love in palpable ways, and to rest in his shalom.

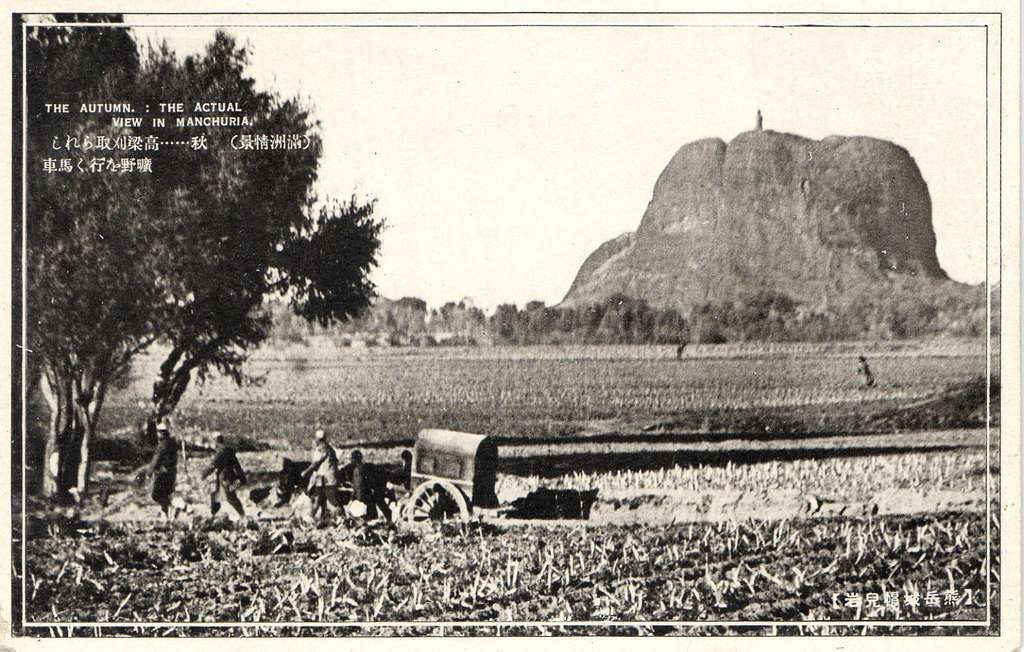

California landscape by Thomas Hill (1829-1908)

Notes:

- Isaiah 32:17

- Matthew 25:21

- Matthew 5:14-16

- (https://www.eauk.org/idea/five-famous-christians-who-went-to-prison.cfm )

- Psalm 9:9-10

- Psalm 145:17

Image credits: http://www.publicdomainpictures.net (5); http://www.dailyverses.net; http://www.picryl.com.

Do sign up below for the monthly newsletter–and thank you in advance for becoming a subscriber!